When the SOS Signs of Suicide program launched in the United States more than 20 years ago, its approach to preventing suicide among young people was considered unorthodox.

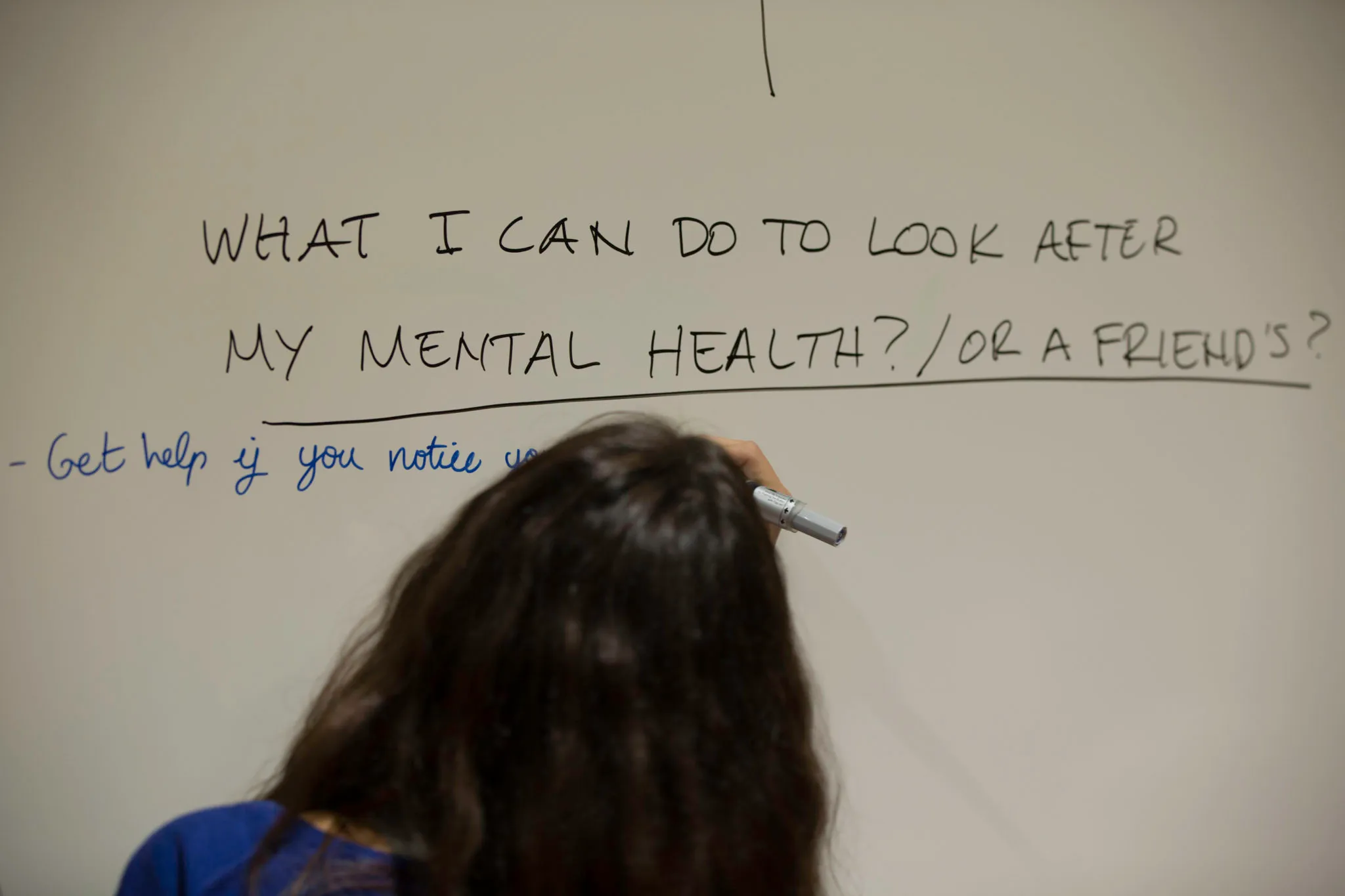

One of the first programs of its kind, SOS trains students to identify the warning signs of depression and suicide among their peers and gives them guidance on how to help. Back when it started, the program went directly against the generally accepted belief that only adults were qualified to help a young person through a mental health crisis.

“When SOS came along, it was very uncommon to be teaching students about the signs they should be looking out for in a friend,” said Meghan Diamon, a licensed clinical social worker and SOS program director at the nonprofit Riverside Community Care in Massachusetts. “But the need was there because friends are much more likely … to show signs to each other that they’re not showing to the adults in their lives.”

Young People at Risk

Every year, more than 700,000 people across the world end their own life, according to WHO data. The issue is on the minds of world leaders this month, with mental health high on the agenda at the United Nations General Assembly, where governments, nongovernmental organizations, and health agencies are being urged to commit to addressing mental health challenges and their underlying factors.

For young people, the data is stark – suicide is the third leading cause of death for people aged 15–29. As adolescents in many parts of the world start the new school year, juggling everything from academic pressures and the impact of social media to climate anxiety and economic challenges can exacerbate mental health conditions.

But programs such as SOS are proving to be powerful tools in suicide prevention. According to SOS’s data, the program has reduced suicide attempts by 64%.

Learning the warning signs

The classroom-based initiative teaches middle- and high-schoolers how to detect when their peers — or they themselves — are struggling and gives them the tools to reach out to a trusted adult. It provides guided discussion prompts, presentations, and educational videos of acted scenarios and real-life stories of students’ experiences with suicidal thoughts and how they got help to turn their lives around.

One of those stories is Elli’s. When she was only 12, her mental health began to suffer – in part as a result of the relentless bullying she was experiencing at school, in addition to other underlying factors. It wasn’t long before she fell into depression with suicidal ideations. Then, she confided in a friend.

Her friend told Elli’s parents, who were able to get her help. “It was so beneficial having that one person … She didn’t understand what I was going through, but she never left my side,” Elli told SOS. “She saved my life.”

More Referrals, Better Outcomes

In the United States, more than a fifth of high school students reported having serious suicidal thoughts in 2023, with almost double that saying they had experienced persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness.

To help those young people, a web of organizations like SOS exist around the country, working in different parts of the spectrum of mental health needs, from the early – such as recognizing the signs and intervening — to the later, including crisis support.

Hope Squad is another national program that promotes a peer-to-peer approach along with recurring training and community building throughout the school year. Its spokesperson Grace Babula cited initial resistance to its methods – as SOS encountered when it first launched.

“There’s a pervasive fear that this topic is too mature for students, but there is a lot of research that shows asking someone in distress what they are currently going through does not increase the risk of suicide,” she said.

“I think the reality is that students are talking about these challenging things among themselves, so it’s really important to give the youth more credit for what they’re capable of handling.”

Alyssa Wilkinson, a mental health worker who runs Hope Squad programming in St Louis area schools, agreed. “I’m not going to teach a kid empathy when they clearly already have a very strong grasp of it,” she said. “What I’m going to do is teach them how to utilize that empathy and how to make sure they set healthy boundaries for themselves, so they don’t burn themselves out doing it.”

She said the biggest indicator that this approach pays off is that she has heard from kids who “felt like they had a sense of leadership, and like they weren’t helpless in helping their friends.”

First Line of Defense

This strategy of empowering students as the first line of defense is the very factor that many educators believe makes these types of programs successful. Adults who interact every day with students who go through these programs confirm the positive ripple effects this training has had.

Learn more about our work to support mental health.

Lyn Adolfo has been in the education world for 35 years, first as a teacher and now as a social and emotional learning (SEL) specialist. She leads Hope Squad programming in the greater Detroit, Michigan area, in a school system with a large minority ethnic population and a high proportion of people living in poverty, two groups who contend with heightened challenges that affect mental health. Suicides are more common in lower-income areas, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There’s a huge increase in students reaching out for mental health assistance,” Adolfo said of her three years as an SEL specialist. “In 2022, we had 88 referrals from students. As of the middle of this year, I lost count, but it was over 200.”

What’s more, Adolfo added, “every referral that a student brings to me has had a positive outcome.” This year alone, the number of student Hope Squad leaders being trained to recognize struggling peers has doubled, she noted.

Helping young people build the life skills they need to protect their own mental health is one of the key pillars of WHO’s LIVE LIFE initiative for suicide prevention, which provides evidence-based technical guidance for suicide prevention to everyone across health, community, and other settings.

“Suicide is complex. For suicide prevention, we need a concerted whole-of-society and multifaceted response,” said Dr Alexandra Fleischmann, a scientist in WHO’s Mental Health and Substance Use Unit. “Importantly, the socio-emotional skills of young people need to be fostered to help them with problem-solving and coping.”

Dr Fleischmann noted that although WHO has not carried out a systematic review of how effective peer-led interventions are at bringing down suicide rates among young people, “reports about peer-to-peer programs seem promising.”

Rising Demand

The Second Wind Fund in Colorado was created in 2002 in response to the suicides of four students at a single high school in one school year in the Denver metro area. Since then, the organization has served more than 9,000 students who need immediate mental health support with more than 60,000 hours of therapy.

Suicide rates in Colorado are the lowest they’ve been sine 2007, the latest data shows.

“Therapy is a major intervention when addressing youth suicide,” said Gabriel Guillaume, Second Wind’s executive director, but the group recognizes that youth often can’t access treatment. “The organization built its mission around the idea that we’re going to reduce incidents of suicide among children and youth by removing social and financial barriers to treatment.”

That means anything from paying for counseling services with therapists to helping young people go through the steps of finding a qualified mental health professional.

Second Wind Fund acts as a connector, receiving requests for students in crisis and bridging them with specialists right away to get the support they need. The need for this support is clear: The group reports a 58% increase in referrals just in the last year.

Guillaume said the organization’s method of working with a network of therapists, rather than having an in-house therapist, allows for the therapy work to start much more quickly than it would in a free clinic. The majority of kids who come to Second Wind display marked improvements as early as their eighth session, he added.

“We can serve people all across Colorado, because we are not one singular office,” Alex Koon, development manager, said. Each eligible student is able to start therapy within seven days. “It’s worked really well,” Koon added.

Like Second Wind Fund, Hope Squad and SOS Signs of Suicide have also seen an increase in referrals over recent years. For Guillaume, that’s both bad news and good.

Rising demand means large numbers of young people are still facing mental health challenges. But it also means more are willing to reach out for help.

“Part of the message here is that this remains a crisis,” he said. “But there’s real innovation taking place right now on how to address that crisis, and … it’s very much what drives us each and every day.”

About the WHO Foundation

The WHO Foundation helps to advance the work of WHO’s special initiative for mental health and PAHO’s regional suicide prevention initiative with the generous support of our partners. WHO’s programs on suicide prevention include fact sheets, data, and best practice information, including guidelines for media reporting on suicide.

.webp)